This ritual may be changed or adapted in any way you wish. It is not to be taken as 'holy

writ.' As you can see from the endnotes, I have used several sources to put this together, so by all

means, make any and all changes to make this ritual workable for you and/or your group!

Notes:

1 Cunningham, Scott. Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner.

1988. Llewellyn

Publications, St. Paul, MN, pg. 118.

2 Starhawk. The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the

Great Goddess --

10th Anniversary Edition. 1989. Harper, San Francisco, CA, pg. 225.

3 Fitch, Ed and Renee, Janine. Magical Rites From the Crystal Well.

1984. Llewellyn

Publications, St. Paul, MN, pg. 47.

4 Ibid, pg. 48.

5 Ibid, pg. 48.

6 Ibid, pg. 48.

7 Ibid, pg. 48. I have taken this passage from a ritual written for a group and

adapted it for a

solitary. For a group working, change 'me/I' back to 'us/we.'

8 Ibid, pg. 49. See note above.

9 Conway, D.J. Celtic Magic. 1990. Llewellyn Publications, St. Paul,

MN, pg. 27.

10 Ibid, pg. 58.

11 Fitch and Renee, pg. 46.

12 Conway, pg. 58.

13 Ibid, pg. 59.

14 Ibid, pg. 59.

15 Fitch and Renee, pg. 46.

16 Conway, pg. 59.

17 Fitch and Renee, pg. 47. (See note #7.)

18 Conway, pg. 59.

19 Fitch and Renee, pg. 47.

20 Conway, pg. 59.

21 Fitch and Renee, pg. 47. (See note #7.)

22 Conway, pg. 59.

23 Fitch and Renee, pg. 47.

24 Conway, pg. 59.

25 Fitch and Renee, pg. 47.

26 Conway, pg. 59.

27 Dunwich, Gerina. Wicca Craft: The Book of Herbs, Magick, and

Dreams. 1991. Citadel

Press, New York, NY, pg. 85. The original chant used the words "the Great Solar Wheel"

instead of "the Wheel of the Year." Feel free to change it back if you prefer.

28 Conway, pg. 59-60.

29 Ryall, Rhiannon. West Country Widda: A Journal of the Old

Religion. 1989. Phoenix

Publishing Inc., Custer, WA, pg. 16. If done by a mixed-gender group, a male would hold

the chalice and a female the athame.

30 Ibid, pg. 17. The original just said "bountiful womb." I added "of the

Goddess" because I

thought it sounded better. As in the above note, if this is performed by a mixed-gender

group, a woman would hold the athame and a man the plate.

31 Dunwich, pg. 85.

32 Farrar, Janet and Stewart. A Witch's Bible Compleat. 1981.

Magickal Childe Publishing, Inc., New York, NY, pg. 150.

�

- by Brighid MoonFire

Darkness falls

and the creatures of the night

begin to take their place.

The owl and raven

take their flight.

Death oracles upon

the wingspan of eternity

The Elder tree sways in the chilling wind

under the light of the waning moon.

Its gnarled branches

touches the minds of humans,

spreading bizarre images of Persephone's kingdom

throughout their dreams.

The wisdom of the Earth

rests within the womb

of the one robed by the night.

Her name whispered throughout the centuries.

Upon the wind --

riding across the waves

Veil, scythe, and scissors

are by Her side.

To reign supreme upon Her throne

Hecate, Lilith, and Cerridwen.

The Crone

�

FOLKLORE &

PRACTICAL USES: BIRCH

by Muirghein ó Dhún Aonghasa (Linda

Kerr)

Betula alba L. or B. pendula Roth - European White Birch. Native of Europe and

Asia Minor,

from Sicily to Iceland. Planted across United States.

B. papyrifera Marsh. - Paper or Canoe Birch. Across North America near northern limit

of trees

from NW. Alaska east to Labrador, south to New York, and west to Oregon; N. Colorado and W.

North Carolina; to 4000' or higher in southern mountains.

B. lenta L. - Black or Sweet Birch. S. Maine southwest to N. Alabama and north to

Ohio; S.

Quebec and SE. Ontario.

B. nigra L. - River, Red or Black Birch. SW. Connecticut south to N. Florida, west to E.

Texas,

and north to Minnesota; Massachusetts and S. New Hampshire.

B. occidentalis Hook. - Water Birch. NE. British Columbia, east to S. Manitoba, and

south to N.

New Mexico and California.

Description & Uses

Called the 'Lady of the Woods' by the English poet Coleridge, the birch is an elegant tree

with a slender trunk, light branches, and delicate leaves which flutter in the slightest wind. But

the most notable feature of the birch is its bark, the color of which gives each species its name.

The river birch is easily distinguished even in winter because of its rather tattered and fluffy

look; its bark peels off in small pieces.

The smooth outer bark of the northern paper birch was used by the American Indians for

making canoes and wigwams. This bark, although thin, is quite strong and resistant to water.

After selecting the largest and smoothest trunks in the spring, the Indians cut sections of the bark

and pried them off with a wooden wedge; these would measure about 10-12' long and 2-9" wide.

These sheets were stuck together with the fibrous roots of the white spruce, which had been

soaked in water to make it supple. The seams were then waterproofed by coating them with the

resin of the balsam fir. The resulting canoes were lightweight -- a 4-passenger size weighed only

40-50 pounds.1 John Burroughs said of this canoe, "The design of a savage, it

yet looks like the

thought of a poet and its grace and fitness haunt the imagination."2

The Indians also used the wood of the paper birch for snowshoe frames, and rolled the

bark into a taper to burn to keep away mosquitoes. The paper-like bark was useful for kindling a

fire, and also for a moose-calling horn, a straight tube about 15" long and 3 or 4" wide at the

mouth, tied about with strips of more birch bark. The bark makes a unique natural paper, but

Peattie suggests looking for a fallen tree, as the tree does not replace its outer living layers.

Instead, bands of an ugly black scar tissue are formed.3

The paper birch only occurs in the northern states and Europe; however, a similar species

known as the southern paper birch is found solely in the high mountains of North Carolina and

eastern Tennessee.4

The black birch is unusual in that its bark and twigs have a distinct wintergreen flavor.

"So closely does a distillation of the bark and twigs resemble the true oil of wintergreen, that

commercially at one time it had almost taken its place. Now, however, most of this oil is

prepared artificially by chemical means."5

The bark of the white birch has been used for centuries for various purposes; rolls of

birch bark have even been found when excavating Mesolithic sites. The bark was used by the

Scottish Highlanders to make candles, and Northumbrian fishermen went spearing at night with

birchbark candles or torches.6 Its twigs were also used for thatching, wattles, and

broom making,

and in the manufacture of cloth. The bark contains tannic acid, and is used for tanning, giving a

pale color to the skin. Birch Tar oil, manufactured in Russia, is useful for keeping away insects

and preventing gnat-bites.7 The leaves make a good humus if composted. In

Russia, the wood

was used for making charcoal, shoes were made from the bark, and an alcoholic drink was

distilled from the unopened leaf buds.8

Medicinal & Food

The young shoots and leaves of the European birch are astringent, diuretic, and

diaphoretic. The shoots and leaves can be used to make a laxative, and the leaves are good for

gout and rheumatism. To eliminate gravel and dissolve kidney stones, take 1 to 1 1/2 cups of the

leaf tea a day. Supposedly a decoction of the leaves is good for baldness, but I wouldn't place too

much faith in this remedy! It may work better for insomnia; take the tea before going to bed as a

mild sedative.9 Birch is quite useful for skin problems, and can be used in a sitz

bath. Boil 2-5

lbs. birch leaves with enough water to cover for 1-2 hours in a cotton bag or pillow case. Put this

in enough hot water to reach the waist in a bathtub, and drench your shoulders, neck, back, arms,

and face with the bag for as long as you feel comfortable. If you feel weak or too relaxed, go

ahead and get out. Do this once or twice a week 30 times consecutively for internal and external

complaints.10

A lesser known species of birch, B. pumila, was used by some American Indian

tribes,

who gathered the conelike fruiting structures and boiled them to ease menstrual cramps. They

also roasted these cones over a campfire and inhaled the smoke to cure nasal

infections.11

The black birch has similar medicinal properties to the European birch, with the added

benefit of being an anthelmintic, meaning it expels worms. Birch tea, made from an infusion of

the leaves, was used by the American Indians for headaches and rheumatism, and a decoction of

the bark and leaves was brewed for fevers, kidney stones, and abdominal cramps due to gas. A

tea decocted from the inner bark helps diarrhea and boils, and for external use on burns, wounds,

and bruises, apply the tea as a poultice.12

Birch contains methyl salicylate, which has counter-irritant and analgesic properties, so

the old remedy for rheumatism is justified. As the skin absorbs this chemical, a poultice is quite

useful for skin irritations and minor wounds. Modern pharmacists combine synthetic methyl

salicylate with menthol in creams and liniments to relieve the pain of musculoskeletal conditions

such as rheumatism, osteoarthritis, and low back pain.13

Due to its wintergreen flavor, birch bark tea was used by the settlers as a gargle and

mouthwash to freshen their breath, and in the Appalachians and the Ozarks today, people chew

twigs of the black birch to clean their teeth. Rodale's even suggests that people who want to quit

smoking consider chewing on a birch twig to relieve the oral fixation.14 The

inner bark can be

chewed like chewing gum, and, being rich in starch and sugar, is a good emergency food if

you're out walking in the woods.

The European and black birches are valued for their sap; beer, wine, and vinegar are

made from it in some parts of Europe.15 Here is a simple recipe made from the

black birch. To

tap the tree, make a cut in the stem when the sap is rising, around March. The sap will flow

freely, and 16 to 18 gallons may be drawn from one large tree. To prevent harm to the birch,

though, pull only what you need, and stop up the incision afterwards.

Birch Beer: Place 4 quarts of finely cut twigs or inner bark into a 5-gallon crock. Add 4

gallons of water or birch sap (better) and bring to a boil. Stir in 1 gallon of honey (add some

cloves and lemon peel, if you like), and remove from heat. When cool, strain to remove the bark

and twigs. Keep the liquid in the crock, and place 1 yeast cake on a piece of toast and float it on

the liquid. Cover the pot, and let the mixture ferment for about 1 week, until it begins to settle.

Bottle the Birch Beer, and store in a cool, dry place. It can be kept for several months, up to a

year, depending on storage conditions.16

Folklore

The birch is a tree of magical powers; witches were said to have ridden on broomsticks

made of birch on Walpurgis (Beltane) Night,17 and birch was also a common

May Pole. To

protect against enchantment and fairies, the Irish and Welsh hung crosses of birch over their

doors. Artillery arrows, bolts and shafts were made of birch; the 'mana,' or magic, of the birch

may have been thought to give them extra power.18

One of birch's more traditional uses has been for brooms and switching rods: Grigson

proposes that the magic of the birch, and its companion, the broom plant, helped sweep evil as

well as dirt out of the house. Likewise, in disciplining children, maybe the birch also literally

thrashed the Devil out of them!19

The birch's name may have originated from the Latin word batuere, to strike. The

birch

certainly has a long history as an instrument of discipline; children know birch switches all too

well, and supposedly Christ was beaten with birch rods. We get our word 'fascist' from the

fasces, a bundle of birch sticks tied to an axe with the blade projecting. These were

carried by

Roman soldiers, and symbolized the state's authority to punish by flogging (the sticks) or putting

to death (the axe).20 These fasces were also carried by the lictors, who swept the

way for the

Roman magistrates with birch twigs.21

But from this discipline comes new beginnings: "As though Birch were a passport back

to life, the dead sons who return in the ballad of the Wife of Ussher's Well, are wearing

birchen

hats from a tree which

...neither grew in syke or ditch

Nor yet in ony sheugh;

But at the gates o' Paradise

That birk grew fair eneugh."22

Notes:

1 Rodale's Illustrated Encyclopedia of Herbs. Edited by Claire

Kowalchik and William H.

Hylton. 1987. Rodale Press, Emmaus, PA, pg. 44.

2 Green, Charlotte Hilton. 1939. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill,

NC, pg. 87-88.

3 Peattie, Donald Culross. 1950. A Natural History of Western Trees.

Bonanza Books, New

York, NY, pg. 385.

4 Green, pg. 88.

5 Ibid, pg. 95.

6 Grigson, Geoffrey. The Englishman's Flora. 1955. Phoenix House

LTD, London, England, pg.

244.

7 Grieve, Mrs. M. A Modern Herbal (2 volumes). 1931. Dover

Publications, Inc., New York,

NY, pg. 103.

8 Brimble, L.J.F. 1946. Trees in Britain. MacMillan and Co. Ltd.,

London, pg. 236-238.

9 Lust, John. The Herb Book. 1974. Bantam Books, Inc., New York,

NY, pg. 118.

10 Hutchens, Alma R. Indian Herbology of North America. 1973.

Merco, Ontario, Canada.

Published in London, England, pg. 38-39.

11 Rodale's, pg. 44.

12 Ibid, pg. 44.

13 Ibid, pg. 44-45.

14 Ibid, pg. 44, 46.

15 Grieve, pg. 103.

16 Weiss, Gaea and Shandor Weiss. 1985. Growing and Using the Healing

Herbs. Rodale Press,

Emmaus, PA.

17 Lust, pg. 581.

18 Grigson, pg. 244.

19 Ibid, pg. 244.

20 Lust, pg. 581.

21 Brimble, pg. 236.

22 Grigson, pg. 244.

�

LUNAR ENERGIES &

ESOTERICA:

BIRCH

by Freya Laughing Bear

Just as January marks the beginning of the Gregorian calendar, so does Birch, or Beth,

begin the Celtic lunar calendar. It is a time of new starts and a realigning of Self. The primary

energies of the Birch moon are awareness, sensitivity, and responsibility. We must attempt to

learn what they mean and exactly how to apply them to our everyday lives.

These characteristics build upon one another. First, it is necessary for you to become

aware of your actions and the effect they may have on others; but you must also be aware of the

actions of others and their effects upon you. It is from this awareness that you develop sensitivity

-- not only sensitivity to yourself and your needs, but also to others and their feelings and needs.

This results in a responsibility to be true to yourself and to others, and a willingness to take

responsibility for your own actions. All these characteristics are components of authority,

tempered with compassion, and self-discipline. The problem is that most people have trouble

with both these concepts.

One special characteristic of the Birch tree is that it is self-propagating -- that is, it

recreates itself. In many ways, this is true about ourselves. In order for us to survive in a rapidly

changing society, it is sometimes necessary to concentrate on ourselves and our survival.

However, if you have a job, you run into the authority problem. For example, while you may

want to do one thing, your superior may need you to do something totally different. This is when

you may find yourself questioning his or her authority, and your immediate reaction is to rebel.

However, the self-discipline that you have learned (and hopefully practiced) will help you accept

his or her authority, keep from reacting, and do what you need to do. I know this is difficult, but

remember; discipline, discipline!

On the other hand, when you are in a position of authority, you must discipline yourself

and learn to be authoritative without being over-bearing. The Birch rod has been seen as a

symbol of authority, but it should always be tempered with compassion. You may have the right

to make the rules, but be careful not to become a tyrant to those under you.

The glyph for this moon is "I am a stag of seven tines." This mythological stag has lived

14 years, and has acquired somewhat of a royal status. As a result, he also acquires a certain

amount of authority. This symbolic ruler does not and cannot rule with a steel thumb and expect

results; he must feel compassion for his followers and be aware of and sensitive to their needs

and desires.

So after battling the fears and uncertainties of Elder and having to deal with the

headaches of Christmas, that breath you've been holding through the last part of the year is now

released, and things will 'break loose.' It is now time to sit down and begin to integrate and

recreate yourself.

Use the discipline of this moon to stick to your resolutions, and begin that long-awaited

exercise program. Let the Birch teach you compassion, sensitivity, and understanding, and the

true meaning of authority. And remember, the Birch tree itself can help you through the

difficulties of this moon.

�

by Arion of Methymna

The first moon is the Birch moon; Birch and Bay Laurel being the traditional royal life-trees

-- the 'king's tree.' The condition of the Bay and Birch in a place was seen as a reflection of

that realm's rule and authority (Richard II, Shakespeare). So Birch is the tree of

authority.

The person satisfied with such an answer gets the right to be scourged with a Birch

wand.

Why is Birch the tree and moon of authority? Why is it the first moon and tree? Why is

the Birch associated with kings and rule? The answers are not in the first paragraph, only clues to

them. Start with some simpler questions:

What is a king or ruler? What does he do?

What is authority -- really? What makes one an authority?

(Is power the same as authority? Is influence? Is it just specialized knowledge, or having

more knowledge than the next person, that makes authority?)

Power is a poor replacement for authority, likewise influence, though both may result

from authority. Any specialized knowledge is like an echo of only part of the answer to "What is

authority?" The best catalysts to anything like an answer are, appropriately, three:

1) The mascots for this moon are Janus the Previewer and Reviewer, and Argos of the

Hundred Eyes.

2) The bark of the Birch grows around numerous boles in such a way as to form 'eyes.'

3) Lastly, the most common Greek word for authority is .

Exousia breaks down thusly: ek-out of, from; ousia-being (a participle of 'to be'). So

authority is a natural, innate, reality, an extension of one's being, not something added-on like

specialized learning or circumstantially valuable trivia. We're dealing then with internal realities,

intangibles, the subjective (which was not always the dirty word it has been for the last 200

years). The primary authority then, is authority with oneself. And this "authority" is a natural

extension of a person. So, is it charisma, then? No, for to charm is power and influence but does

not involve authority with oneself or one's self.

Argos had eyes all around his head, so that he was ever alert, watchful, vigilant, aware.

Janus guarded the year-gate. He was aware of what had been and looked upon what was yet to be

-- simultaneously. Both were keepers of something precious, holding great responsibility. Both

were watchful, aware of all about them, and not by means artificial to them; they could not

confine their awareness to just one path or way, one direction, one perspective. They were aware

and sensitive and responsive to all about them.

The eye is often a symbol of wisdom -- of responsible awareness over against the knee-jerk,

reactionary, unidirectional awareness of the adolescent. The rebelling adolescent reacts

against another and, in doing so, confirms the authority of this other. Reacting is not responding,

is not being responsible. A person reacts whose authority is external (a book, a man in

gilt and

trappings, a group in business suits, a person long dead), and whose strength and discipline

depend on the circumstance of that external authority -- for otherwise inside the reacter is

anarchy waiting to happen: The Gerasene Demoniac of the New Testament's Gospel of Mark

(Mark 5:1-23). He must be an anarchy. He perceives, senses, so much, but without a

center,

without an internal point in which to trust, all is a buzzing confusion. Inside, no part of the

reacter will take responsibility.

Responsibility, then, is involved in authority, in the Birch moon; though more needs to be

said of responsibility later.

Awareness, vigilance, within and without, before and behind, is also a syllable of the

Birch's true name -- as is obvious from the mascots Janus and Argos. In most 12-step programs

the combination of awareness and responsibility is expressed in phrases like "regularly engage in

a fearless and searching moral inventory of ourselves...continued to take responsibility for our

own recovery, and when we found ourselves behaving in patterns still dictated by (our

condition), promptly admitted it. When we succeed, we promptly enjoyed it..." (From the

Welcome Pamphlet of the Survivors of Incest Anonymous.) Failure of awareness, in

psychological and counseling jargon, comes out as transference, projection, denial, inappropriate

emotional reactions, some histrionic behaviors. But failure of awareness, no matter the form, is a

matter of intention -- some part of the person chooses not to receive or acknowledge input. So

awareness is indivisible from responsibility.

There is also sensitivity involved, and this is the most difficult aspect to describe.

Awareness, and a facile form of responsibility, without sensitivity, is incarnated in the

facade of Mr. Spock of the old Star Trek series. While he was aware of practically everything

that occurred around him, he labored at insensitivity -- at being unaffected. Events and crises had

no impact on his manner or behavior. Pity, or compassion in its popular sense, is not the

sensitivity of Birch. A sensitive person is teachable, willing to be vulnerable, open, willing to be

as aware as organismically possible and open to being affected by what he or she becomes aware

of. Even to the point of 'com-pas-sion,' the point of 'feeling-with' others (though this

point, and

all it entails, is the lesson of another moon). Even to the point of 'feeling-with' another, not

just

sadness, but all four basic emotions: mad, sad, glad, and afraid.

A Birch disciple is aware of all he or she can do, and senses, is sensitive to, all he or she

can be. Without sensitivity, understanding is impossible; a person becomes merely a chronicler, a

data collector. Sensitivity is vital, else the Medusa of simple self-awareness will turn one to stone

without the mirrors that others provide.

This awareness and sensitivity is not sufficient. People with dazzling awareness and

alertness, as well as incredible sensitivity, end up in mental institutions, in codependent or

caretaking relationships, or as stunted adolescents with no self of their own. Neither sensitivity

nor awareness alone can calm the anarchy inside nor govern or prioritize the demands and

anarchy outside. They just make both realms into more acute sources of pain.

What turns such anarchies into communities is responsibility -- the ability to respond.

A king is a ruler, a regulator, the one with the regulae or rules. He or she takes the

sensitivity that a life of awareness provides and he or she chooses what response is appropriate to

him or her. And in the calm, not dispassionate but non-judgmental, inner stillness is the

achievement of self-authority, the fulcrum of right action and creativity. A king must be his own

regulator first, else he can be no one's ruler: To accept, with a severe scrutiny. To reclaim the

qualities once considered foul, scary, obscene; not acting from them necessarily but not making

fear of them your master, and not making them monsters. To reconsider those qualities once

considered angelic, noble, fine, with a steady and consistent awareness that pierces to the core of

things, to the ambiguity in motives. Just like this moon's mascots, who see clearly; aware, open,

and responsive, not condemning or disowning any input...so also does a Birch-king or

Birch-queen not close their eyes -- any of them -- out of fear or laziness: To do so leads to

reacting

again and to the diminishing of sensitivity.

Being responsible with as full an awareness as possible is a discipline, it is being a

disciple, being teachable. If you react to the demands or coercions without, or the demands and

emotion-gales within, you are a slave. If you can actually choose how you will respond to the

clamor, and you know who is making the choice -- whose is the responsibility -- then you have

become the Birch's disciple.

How can a person learn to be responsible? Well, how do you learn to breathe? There is no

simple, or complex, how-to. By making choices and being aware of the choices you make. By

you yourself making yourself accountable for those choices. By you yourself becoming the one

to judge the appropriateness of your actions. If this all sounds like a result or end rather than a

method or means, well...that is because again -- heresy of heresies -- there is no "how-to," no

technique. How authority is achieved is an individual thing, and this is only appropriate since we

deal with Birch -- the loner.

One or two other concerns.

Birch is the rune of living authority, self-mastery, the solitary, the aloof one. Yet Birch is

also the gatekeeper for communion and true compassion. How?

Well, remember Hamlet and King Lear? Oedipus? In each

instance, Claudius, Lear, or

Oedipus, the status of the king or malfeasance in the kingship was echoed in the land and the

vassalage. A king was his universe, his realm, in microcosm. Likewise, an honestly aware and

sensitive person contains or claims the objects and people about him or her, instinctively -- the

acquisitive mode to human perception. More to the point, an honestly aware and sensitive person

acknowledges their capacity to resonate at some level with everything that exists -- the empathic

mode of human perception that Terrence touched on in the claim "I am a man, nothing human is

alien to me."

Perhaps a simpler way to express this is to say that the king does not have to go disguised

among his people to understand them -- he need only go wandering through the land of his own

psyche to see he is capable of everything any human being has ever done -- he has a

deep and

real commonality with all creation. A reciprocal Heisenberg Principle, and one not confined to a

human-to-human realm, but an undeniable corespondence of human to created entity. So Birch is

the tree of the One, the individual and the totality, distinct from everything else and indivisible

from everything else. Also, in order to appreciate community, communion, one must be a Self,

be their own person. One must have learned the initial lessons of the Birch moon.

Two more points need to be mentioned.

First: The lessons of the Birch moon are one lesson; awareness, sensitivity, and

responsibility are reference points for one capacity and range of behaviors. Listing three aspects

for the Birch-moon lesson is a concession, a compromise in the face of the limits of the English

and Romantic language and thought patterns.

Second: What is given here is an exposition of an initial level in the mystery that is the

first moon. There is more, involving a deepening into what is called intuition and what is blithely

labelled "divine-human dialogue" and the healing of the thought (or wish)/action split that so

plagues westerners' behavior (the 'what I think to do I never get around to' and 'I had meant to

do that, but...' syndrome). All these fall under Birch's lesson of authority.

Arion of Methymna is a former student of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary,

and has also been active in the Craft for 10 years.

�

FOLKLORE &

PRACTICAL USES:

ROWAN

by Muirghein ó Dhún Aonghasa (Linda

Kerr)

Sorbus aucuparia L. - European Mountain Ash. Native of Eurasia, grows wild in the

deciduous

forests of Europe and Asia; naturalized in SE. Alaska and across S. Canada to Newfoundland,

and from Maine to Minnesota and California.

S. americana Marsh. - American Mountain Ash. W. Ontario to Newfoundland, south to

N. Georgia, and northwest to N. Illinois and Michigan; to 5000-6000' in southern

Appalachians.

S. sitchensis Roem. - Pacific Mountain Ash. Coastal southwestern Alaska, through

Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and northwestern California.

Description & History

The rowan is a member of the Rosaceae, or rose, family, and like the rose, is valued

for

its beauty. The rowan is commonly grown in gardens, but is just as lovely in its natural setting.

"So attractive is it that the mighty conifers seem as if they had as their first business the

setting-off by contrast, with their unmoving darkness, the lively charms of this little tree...filling

in all

the sunny spaces between their crowding shadows."1

A small tree, the rowan rarely grows past 30 feet. Its compound leaves of 9-17 leaflets

each are similar to a sumach, and also to an ash; thence its common name, mountain ash. The

rowan produces small white flowers in flat-topped clusters, giving way to its characteristic bright

orange-red berries in the fall, which remain throughout the winter. The name 'rowan' refers to

these berries, being derived from an old Scandinavian word meaning red.2

These berries are an important winter food for birds, especially cedar waxwings, who eat

them when other foods are scarce.3 In Europe, fowlers (bird catchers) used the

rowan's fruit as

bait for their traps. The berries were also made into birdlime, a sticky substance smeared on

branches to capture the birds.4 This practice gave the European rowan its specific

name,

aucuparia, which is derived from the word auceps, meaning a fowler, or 'to catch

birds.'5

The rowan's wood is tough and elastic, but the tree is usually too small for the wood to be

of much commercial importance. In the past, the European species was used for poles and hoops

for barrels, due to its flexibility.6 John Evelyn wrote that fletchers

(arrow-makers) recommended

rowan wood for bows, next to yew.7 Later, the wood was used in turnery because

of its fine grain

and ability to take a high polish.8 The bark and berries can also be used in

tanning, and to make a

black dye.9

Folklore

The rowan has many country names, the most common being quickbeam or quicken.

These names derive from the Old English 'beam' meaning 'tree,' and 'quick' as an adjective in

the sense of 'lively'. The quickbeam was a tree endowed with life. 'Quicken' also means to come

or return to life, and as such, the tree used in an ancient ritual to restore fertility to barren or

bewitched land, was arguably the rowan.10

The rowan's other names are equally magical: wicken, wiggen, wicker, witchen,

witch-wicken, witch-tree, and witchwood. According to Grigson, the 'witch' names come from

the Old

English 'wice' or 'wic,' meaning a tree with flexible branches or timber. Grigson believes,

however, that "the sense of 'witch' was undoubtedly felt in the wic names for the

tree."11 And

according to Edward Step, the name 'rowan' may be derived from the old Norse runa

meaning 'a

charm.'12

The rowan was considered a powerful tree for protection in the old world. The Irish

nailed pieces of rowan over their doors on May Day to keep out fairies and witches, and placed it

around the butter churns and in the milk pails to prevent theft of the milk and butter. Rowan was

commonly used in Yorkshire, the Isle of Man, and the Highlands and Islands, for similar

protection on May Day. In various parts of England, butter and cream were stirred with a

rowan-stick, and special cakes were made over a rowan fire.13

Rowan kept the dead from rising, and was planted in graveyards and built into coffins and

biers. Rowans were also planted around houses, probably to keep witches and fairies out. "In

Wales, if you were foolish enough to step into a fairy circle, only a stick of rowan laid across the

circle prevented you from staying there a year and a day."14

Witch-wands, or divining rods, were made of rowan for metal divining, although the

hazel works best for finding water. A piece of wood carried in the pocket protected one from

ill-wishing and elf-shot afflictions of rheumatism. The wood was also used for walking sticks

because of its power against 'fascinations.'15

Finally, rowan figures in the story of Diarmuid and Grania, from the Irish Finn Cycle.

"On their flight from Finn, Grania's husband, they stay in the wood of Dubhros by permission of

the fairy guardian of the Quicken-tree, who is thick-boned, large-nosed, crooked in the teeth,

with one red eye in a black face. By day he sits at the foot of the tree, by night he sleeps in the

branches. The tree had sprung from a berry dropped by the Tuatha de Danaan. Grania asks for

some of the wonderful berries, and to get them Diarmuid has to kill the fairy

guardian."16

Medicinal & Food

The berries of the rowan are the most useful medicinally. The ripe berries make a good

gargle for sore throats, inflamed tonsils, and hoarseness, being soothing to the mucous

membranes.17 An infusion of the berries is also useful for

hemorrhoids,18 and the fresh berry juice

is mildly laxative.19 The ripe berries contain citric and malic acids, and was at

one time used for

scurvy.20

The berries become astringent when cooked into a jam, and will help mild cases of

diarrhea. One of the sugars in the fruit is sometimes given intravenously to reduce the pressure

to the eyeball in glaucoma.21

The bark, which is also astringent, is good for diarrhea and vaginal problems. The bark of

the American rowan has similar properties, and was once used as a tonic in fevers "of supposed

malarial type," where it was often substituted for cinchona bark,22 a Peruvian

tree which itself

contains quinine.23

The Welsh used the berries to brew ale, and they can also be made into beer, perry and

cider. If you have rowans in your area, try making jelly from the berries; it's said to be excellent

with cold game or wild fowl.24 When roasted, the berries can be used for a coffee

substitute and

are better than chicory and poor quality coffees.25

Pick the berries in the late summer, when they ripen into a bright red. The bark can be

gathered in the spring or fall. Try the berries in this liqueur recipe:

Rowan Berry Ratafia: Thoroughly clean 1 lb. of rowan berries, put them in a bowl and

mash them with a fork. Sprinkle 1/2 lb. of sugar on top and stir into the mash. Put a cloth over

the bowl and leave it for a few days. Then add 2 pints of vodka and transfer to a preserving bottle

or jar. Add a few herbs to taste (the berries are bitter; try orange or lemon peel, mace, and

cinnamon), make sure the bottle is securely closed and leave for a month. Filter and add sugar to

taste. Bottle and age for 4-6 months.26

Note: The fresh berries are only available in the last half of the year, and then only if you

live up north or in the mountains. If using dried berries, you'll have to adjust the sugar and

vodka accordingly, since some of the weight of fresh berries is water. Make a small amount first

and adjust to taste.

Notes:

1 Peattie, Donald Culross. A Natural History of Western Trees. 1950.

Bonanza Books, New York, NY, pg. 509.

2 Little, Elbert L. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American

Trees - Eastern Region.

1980. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, NY, pg. 511-512.

3 Green, Charlotte Hilton. Trees of the South. 1939. The University

of North Carolina Press,

Chapel Hill, NC, pg. 296.

4 Brimble, L.J.F. Trees in Britain. 1946. MacMillan and Co. Ltd.,

London, England, pg. 178.

5 Ibid, pg. 175-176, Little, pg. 511.

6 Grieve, Mrs. M. A Modern Herbal (2 volumes). 1931. Dover

Publications, Inc., New York, NY, pg. 69.

7 John Evelyn. Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees. 1664.

8 Brimble, pg. 178.

9 Grieve, pg. 69.

10 Grigson, Geoffrey. The Englishman's Flora. 1955. Phoenix House

LTD, London, England, pg. 176.

11 Ibid, pg. 176.

12 Brimble, pg. 176. This may also be the Scandinavian word mentioned by

Little, pg. 511-512, meaning 'red.' You decide which is most correct.

13 Grigson, pg. 174.

14 Ibid, pg. 174.

15 Ibid, pg. 175.

16 Ibid, pg. 174.

17 Lust, John. The Herb Book. 1974. Bantam Books, Inc., New York,

NY, pg. 339.

18 Grieve, pg. 70.

19 Lust, pg. 339.

20 Grieve, pg. 70.

21 Lust, pg. 339.

22 Grieve, pg. 70.

23 Ibid, pg. 631.

24 Ibid, pg. 70.

25 van Doorn, Joyce. Making Your Own Liqueurs. 1980. Prism

Press, San Leandro, CA, pg. 64.

26 Ibid, pg. 64.

�

In Scandinavian mythology, Balder, the god of Peace, was killed with an arrow of

mistletoe. The other gods and goddesses were quite saddened by this and asked that he be

restored to life. On his return, mistletoe was given to the goddess of love, who decreed that

anyone who passed under it receive a kiss to show that mistletoe was a symbol of love. This

custom apparently became associated with Christmas due to the Druids, who welcomed the new

year with branches of mistletoe.

�

by Freya Laughing Bear

It is within the first few moons that we begin building a foundation that will see us

through the coming year. We begin collecting the building blocks and attempt to learn each

lesson as it is shown to us. In Birch moon, we learned of authority tempered with compassion,

awareness, sensitivity, and responsibility. In the Rowan moon, we build upon that which we have

learned in Birch. For example, the compassion that we learned in Birch now becomes deeper and

generates out toward others -- it becomes more mature.

Along with compassion comes the need to learn communication. It is important to be able

to communicate clearly with ourselves and our low self, in order to bring our prayers and wishes

to fruition. (If you aren't familiar with the low self, read "The Huna System of Magic &

Prayer"

in Issue 5 of THE HAZEL NUT.) Rowan also teaches us

the importance of

communicating

clearly with those around us. As a baby (usually) learns to talk before it learns to walk, we must

learn to communicate (and listen) now, or we won't be able to understand fully the lessons of

future moons.

Rowan is similar to Birch, in that it is a time of conceptions, beginnings, and initiations.

However, the Rowan carries this further, being the "Quickbeam," or "lively tree." Things which

were begun in Birch are either 'quickened' or aborted; that is, either they are hurried along and

strengthened, or they are just ended, since there appears to be no reason to continue on with

them. This choice, however, lies with you.

This brings us to the Mystery of the Seed: "in the beginning lies the ending." The idea is

that one tiny seed that falls to the ground, experiencing a kind of death, roots itself, and begins to

grow. As the plant begins to flourish it produces its own seeds, and, once again, a seed falls off

and starts the cycle over again.

What we see, and hopefully understand, is that this seed represents us in many ways. We

are the 'seed' and what we plant now will grow with us throughout the year. The seed is also a

thought form -- the beginning of a prayer or wish. What is placed into the seed is your choice --

your ideas, your hopes, your desires. This brings into effect the other lessons of Rowan: you

must first conceive your thought form, then clearly communicate your wishes to your low self,

and use the energy of this moon to 'quicken' the life in that seed, so the prayer seed will grow

and bear fruit.

On a more physical level, we are seen as the 'seed' that falls off the 'tree' of our parents.

We fall to the ground and develop our own roots. We then begin to grow and flourish and make

lives for ourselves. We produce our own seeds -- our children -- and then we grow old and die.

However, we are not dead -- we are carried on with our children. There is life and death in the

Mystery of the Seed. In order for the seed to become, there has to be a death of sorts, but there is

also life in the seed; and this continues the cycle. This Mystery touches all facets of life, since

there can be no life without death; just as there can be no death without life. It is an ever-spinning

circle that touches everyone.

�

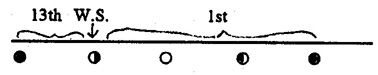

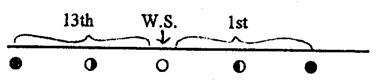

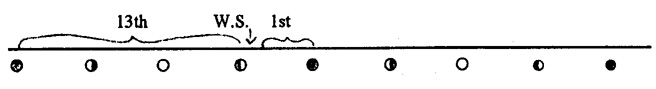

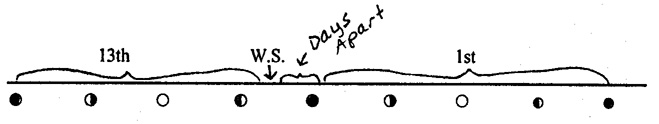

CALCULATING THE START

OF THE FIRST

MOON

by Epona

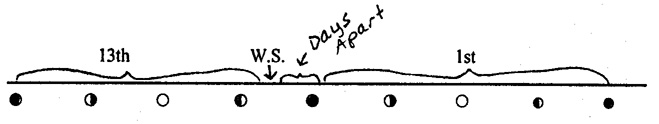

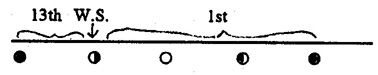

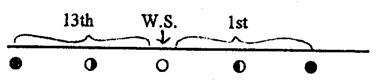

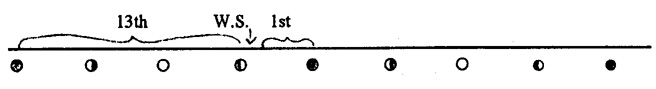

If you do a little math, you'll notice that 13 lunations of 28.5-29 days each cannot

possibly fit into a 364-day solar year, not to mention the fact that the new moon doesn't

conveniently occur when the Solstice does. If the lunars kept rotating through without regard to

the normal year, we'd eventually wind up with the Birch moon beginning in April, and be no

better off than the Romans in 63 B.C. To keep from accumulating such an error, the 13th lunar

(Elder) ends at the Winter Solstice, and the 1st lunar (Birch) begins after the Winter Solstice.

Simple enough, right? Sort of. Read on...

Possibilities:

Waxing of moon in 13th lunar, then more waxing, full moon, and waning moon in 1st lunar.

Waxing moon in 13th lunar, full moon on Winter Solstice, then waning moon in 1st lunar.

Things get tricky when the Winter Solstice intercepts the 13th lunar between the last quarter and

the new moon. The last few days of the lunation after the Winter Solstice may be part of the 1st

moon, or 'days apart' (left over days). If the Birch moon starts at the proper time, the new year's

Imbolc should be in Rowan (Luis), the autumnal equinox should land in Vine (Muin), and the

13th lunar should begin before the Winter Solstice. Two more possibilities:

Without Days Apart:

or With Days Apart:

Things to remember:

- The lunar year ends with the Winter Solstice.

- The 13th lunar precedes the Winter Solstice, and the 1st lunar follows it.

- The 13th lunar and/or the 1st lunar may or may not have the full number of days in a

lunation, and one of them may miss having a full moon.

- The Winter Solstice is not counted as part of either moon, but is a day by itself, and

sometimes the Day Apart.

- The variables which determine the start of the new lunar year (first lunar) depend on how

many days are 'left over' from the thirteenth lunar after the Winter Solstice intercepts it.

- If one of the moons doesn't have a full moon in it, you may celebrate the lunar on the day

closest to the Winter Solstice.

�

by Muirghein & Epona

The Day Apart is the left-over day or days which occur between the Winter Solstice and the

beginning of the Birch moon; sometimes it's on the day of the Winter Solstice. This left-over day

is the equivalent of a leap-day, and serves as a way of lining up the lunar calendar with the solar

year.

The extra day or days are also connected with our modern weekday-names. The Egyptian

year was divided into 12 months of 30 days each, with 5 days left over at the year's end. These

days were not considered part of the normal year, and were named for important deities: Osiris,

Horus, Set, Isis, and Nephthys. The Anglo-Saxons had a similar calendar, and their extra days

were named Tiw, Woden, Thor, Frig, and Seterne. From these last names, plus two other later

ones added by Christian missionaries, come the names of our seven weekdays. (See "The Origins

of Our Modern Calendar," Issue #4 of THE HAZEL

NUT.)

The Day Apart is also seen in the expression, 'A year and a day,' of Irish and Welsh myths.

This stems from the calendar of the British Isles, and denotes a lunar year of 13 lunations of 28

days each (364 days), plus the extra day to make 365. This extra day is the Day of (the birth of)

the Divine Child. This 'son of a virgin mother' is always born at the Winter Solstice (Robert

Graves, The White Goddess, 1948, The Noonday Press, New York, NY, pg. 95), and

refers to the

Sun King, or the Oak King; the young sun who defeats the darkeness of winter, and will grow in

strength until the Summer Solstice. Physically, of course, this symbolies the lengthening of the

days, which occurs after the Winter Solstice.

The Day Apart is thus a day out of time, apart from the normal year, and on such days,

magical things can occur.

The Day Apart, also called the Earth-Mystery Day, is still a magical day, and quite relevant

to

us. Those of the Faerie Faith use this day in a ritual sense, to go to their own special place of

rebirth (best if it is outdoors), and communicate and reconnect with the Earth Mother. To truly

benefit from this, you should first seek out your own spot before that day. This place

of rebirth

will be one where you feel at peace, both with yourself and your surroundings, and it should be

near enough your home so you won't have any excuse not to go. This spot will feel totally right

to you, and may imbue you with a certain feeling of power and energy.

On the Day Apart, go to your spot, and sit in a still, receptive state. Reach out and

communicate with the Earth Mother, and give her a chance to speak to you. Remember your

impressions, but don't attempt to analyze them right now. Stay as long as you feel you need to --

usually a half hour or so. Then thank the elements and the Earth Mother, and return home. Be

sure to write down your feelings and memories at this time.

The Day Apart is the day we choose for this Earth-Mystery primarily because of the heavy

yin energy, with just the beginning of yang coming in right after the Winter Solstice. However,

this ritual is not intended to be enacted only once a year, but at any time you feel is right.

�

- by Epona

Welcome to the circle.

For there is no place

To just begin

Without meeting the ending.

Yet no lesson ends

For it is always present.

(The Mystery of Eternity)

The moon of beginning

Has lessons of ending.

The moon of ending

Has lessons of beginning.

(The Mystery of Being Alive)

One cannot tell of the Birch alone

Without telling of all the others,

As one moon is found in another;

Yet, each is different;

As we, as humans, are alike and different.

(The Mystery of Relatedness)

Yet, one tree leads to the other

And is found in the other

Yet is different:

The energy is found differently in each moon

Yet is present in each moon.

(The Mystery of Time)

In your beginning is your ending:

As you are born, so you are destined to die.

(The Mystery of Seeds)

What is said about one

Can be said about another

But is different

The difference lies not in the defining

But in the experiencing.

For defining is monotonously the same,

But experiencing ENDS at the concept of sameness.

�

by Brighid MoonFire

Some people say that the old ways are dead, but we all know they're wrong. Just because

people no longer believe in them, doesn't mean they don't exist. And then some say that nothing

new is being created, but they're simply not being creative.

I was once told about a goddess whom I had never heard of, named Goddess Asphalta. A

friend had read about Her in a magazine and had adapted Her to her needs. In this particular case

Goddess Asphalta is the goddess of hard-to-find parking places. Think it's silly? Well, the more

you call on something, the more real it becomes, and now many of us call on Goddess Asphalta.

You may think we're silly and ridiculous, but we all get parking spaces. And not just any parking

spaces, but good spaces during the winter holiday shopping season, and that is definitely a

miracle! (Ed. note: to invoke the Goddess Asphalta, say aloud "Oh Goddess Asphalta, grant

me

a parking space!" Upon finding the perfect spot, say "Thank you, oh Goddess Asphalta." You

may also try another deity: "Squat, Squat, parking spot!", but you must always thank

Asphalta.)

So now I bring you someone of my own creation. Last year I was invited to my best friend's

mother's Croning. We were in charge of picking up an entire full sheet cake which would feed

80-100 people, and bringing it out to the site. We put this huge purple-iced cake with a witch

flying in front of a full moon and bats and elaborate decorated sides into my car. It fit in the back

seat, but close enough to my friend's 7-month-old's car seat that he could put his hand in the

cake. Not good. So we put it in the trunk, secured it on every side and angle, and prepared to

make the 2-hour journey.

As we closed the trunk (very carefully, of course), we tried to think of Someone to ask for

help in getting there with the cake intact. But neither one of us had heard of a cake goddess. After

some racking of our brains, the name Goddess Pastrius came to mind. (If any of you get these

type of ideas, don't shout them out in the middle of a grocery store parking lot unless you're

prepared for some very strange looks.)

We made the 2-hour trip around lovely hairpin curves, asking for Goddess Pastrius's help

on

each and every one of them. Then we got to the dirt road filled with washed out gullies, and my

friend held the cake in her lap as we jostled the rest of the way there. At this point we decided to

call upon Goddess Pastrius's helpers -- Her icing fairies. Much to our relief, Goddess Pastrius

and Her icing fairies allowed the cake to remain unscathed, and was the hit of the celebration. So

if you are ever in need of a guardian of cakes and pastries, don't forget Goddess Pastrius. And

don't be afraid to create your own deity in times of need.

�

- by Coll ap Rhiannon

Moonlit path before me winds

between the darkness of the trees.

When soon before the cold track finds,

the waif that seeks to please.

The moons have passed from Imbolc time

'till round with child is She.

And when the Solstice bells do chime,

the fruit is born to thee.

Before the dark of Winter falls,

the Mother withers to the bone.

And on the night when the Oak King calls,

to rest She goes, the Crone.

Weary will the Oak King grow,

until death draws too near.

The Sun returns the Holly foe

to kill the Oak King's fear.

The Sun along his upward track,

the Holly Stag, the Greenman's quest.

Upon the Moonlit path I'm back,

to stir the waif from rest.

�

- by Epona

To Begin

Is to See.

In the Beginning

Is the Ending

In the Seeing

Is the Door

�

Dear Editor:

Heartfelt congratulations on your wonderful publication. We at Luna Press are educated,

informed, and amused! Who could ask for anything more? Well, yes, money! Please

enter the

following gift subscriptions to THE HAZEL NUT beginning with the current issue!

Luminous Blessings!

Nancy F.W. Passmore, LUNA PRESS

Publishers of The Lunar Calendar: Dedicated to the Goddess in Her Many

Guises.

�

BUBBLES FROM THE

CAULDRON

BOOK REVIEWS, ETC.

Ariadne's Thread: A Workbook of Goddess Magic, by Shekhinah Moutainwater.

1991.

The Crossing Press, Freedom, CA. Softcover, $14.95.

- Reviewed by Mirhanda Spellesinger

This is a book about women's spirituality, and as such, most men would probably not enjoy

it. I was put off by her seeming dislike of men, but overall, I enjoyed this book. I did not agree

with everything the author put forward (for instance, I feel her statement that menstrual cramps

and PMS are caused by patriarchal oppression is a step backward. Gone are the days when we

are told that our discomforts are "all in our head" and "if we'd accept our femininity, we'd not

experience menstrual pain!"). Still, this book does make one think about the divine feminine.

Ms. Mountainwater's more militant or bizarre ideas (such as women can become pregnant by

exposing themselves to moonlight!) can be overlooked to gain the wisdom that this book also

contains. I have mixed feelings about this book -- it has good points and bad. Overall, however, I

think women have much to gain by reading it. Be forewarned, though, if you like men (as I do)

you may be offended by parts of Ariadne's Thread.

Samhain Celebration, November 6, 1993, Roxanna, Alabama.

- Reviewed by Muirghein

People began arriving at Roxanna on Friday night, but most folks came in Saturday

afternoon, as the festivities didn't actually begin until 3:00. We began by loading up some hay

bales in the back of Russell's pickup truck; he took several of us on a pretty scary hay ride

through Roxanna! Jeff and Stacey were in charge of the candle-leap game, in which a circle of 12

candles is laid out, each representing one month of the year. As a person jumped over each

candle, Stacey checked to see if the flame sputtered (it would be a bad month) or if it went out

(really bad!). We didn't have many folks brave enough to try this game!

Evening saw a wonderful pot-luck feast, and two contest winners; Coll for best costume,

and

Scott for best jack-o-lantern. The night had turned cold, so after a brief procession

around the top

of the hill to thank the elements, everyone huddled around the bonfire. Several of us warmed up

quite nicely, dancing to Celtic music. In spite of the extreme cold (about 25 degrees), the festival

turned out to be quite fun.